Make it stand out.

-

Dream it.

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

-

Build it.

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

-

Grow it.

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Force

Everyday language can often lead us down the wrong path when pursuing athletic performance.

Success in sport often depends on the athlete’s ability to…

Change their velocity (sprint, jump, etc.)

Change the velocity of an external object (football, shot put, etc.)

Viewing efforts in the gym through the lens of impulse can have a profound effect on your approach to training athletes.

Why do we care so much about change in velocity (ΔV)?

The height of a jump is dependent on the athlete’s velocity at take-off. The distance an implement (football, shot put, etc.) travels is dependent on it’s velocity as it leaves the hand. Because these objects typically start at rest

Sprinter in the starting blocks

Pitcher standing on the mound

How far the ball travels or how fast the athlete moves is dependent on the amount the athlete is able to change it’s velocity.

Sounds simple, right? Let’s take a closer look on how we can train this.

Impulse

Studying the equation below, we can see how changing the impulse on a fixed mass (athlete’s body weight, football, hockey puck, etc) can have a direct affect on the change in velocity.

I = m x Δv

We can be clever and do some substitutions in this equation to make it more easy to see how we can manipulate our training to maximize impulse.

I = F(i) x Δt

There are 3 ways in which we can maximize impulse…

In most sports, taking longer to perform a movement means your quarterback just got sacked or your opponent out rebounds you, so that leaves us with only two options;

Produce a greater peak force

Produce force more rapidly

Note : There are plenty of examples where extending the time an athlete applies a force can be a desirable

Baseball pitcher pushing off the mound

Volleyball outside hitter timing their jump

Hockey player maintaining contact between their skate blade and the ice

Peak Power

Peak power can be a valuable tool but it’s important to note that it doesn’t have quite as strong of a link with changing velocity as we might think. In fact, many of our best efforts can occur when peak power was relatively small compared to other efforts. Conversely, you may perform a movement that registers a personal best in peak power production, but doesn’t result in your best athletic outcome. This happens all the time on the force plates. We see impressive peak power numbers but the mRSI or Jump Height.

It’s important to understand that peak power is measured in one instant during the movement and won’t account for anything before or after.

Take Off

There are distinct phases during a movement

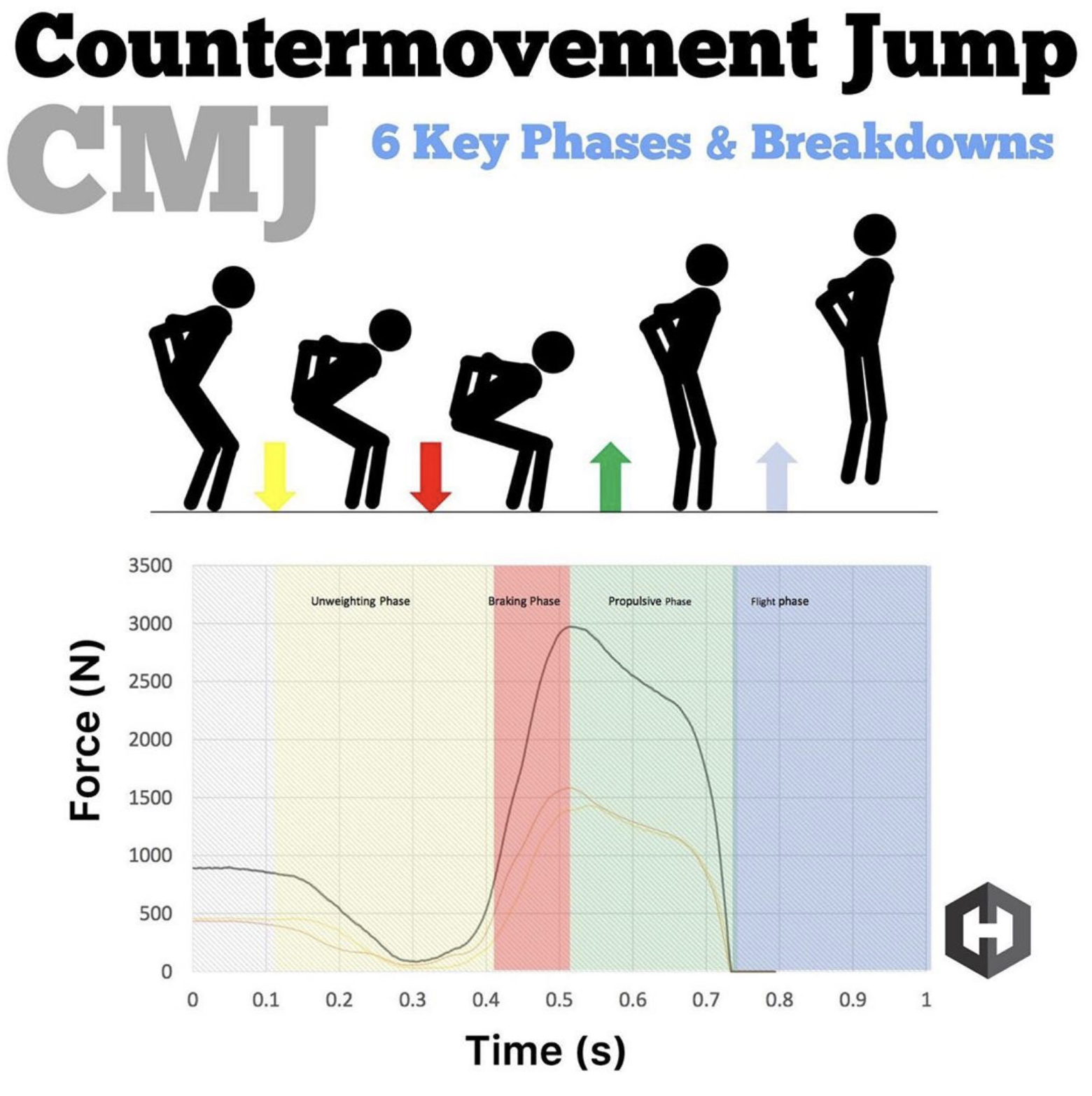

Counter-Movement Jump (example)

Unweighting

Braking

Transition

Propulsion

Landing

Each of these phases can be trained separately

You have many exercise prescription options to choose from to not only train specific phases, but the qualities within those phases.

Analyzing The Counter-Movement Jump

Above is an example of a Counter-Movement Jump (hands-on-hips) represented as a Force-Time curve.At first this can look confusing but I promise that after sitting with it for a few moments it will make a lot more sense.

The different phases of a jump

Quite Phase (1st dark block)

Unweighting Phase (yellow block)

Braking Phase (red block)

Propulsion Phase (green block)

Landing Phase (2nd dark block ‘sudden spike’)

How to Apply If You Don’t Have Force Plates

Although I would love to give you one size fits all program, I think this would be disingenuous. I can however, highlight some principles that will get your gears churning so you can evaluate your current programs and possibly offer recommendations.

View The World Through Impulse Lenses

Whether you’re watching sport or training, apply what you now know about impulse (peak force, time & RFD). How are the actions being performed? Are the movements…

Accelerating quickly or against resistance (high force)

Occurring over a large range of motion (time)

Performed rapidly (Rate of Force Development)

If there are specific qualities that occur frequently in sport, it may be appropriate to include exercises that enhance these qualities in training.

Examples

Hockey requires a mix of skating strides. Acceleration requires short, explosive bursts while top speeds require long pushes where the skater fully extends through his hips and knees.

100m Sprinters get out of the starting blocks using long, rapid and forceful pushes followed by incredibly forceful and rapid strides where contact time needs to be minimal to avoid undesirable “braking”.

Training for both of these athletes may have overlap in exercise selection in the gym focusing on large range of motion, concentric only exercises (i.e. box step-up jumps, non-countermovement jumps) and rapid plyometric movements (i.e sprints, bounds & hops).

Consider The Phases Related to Each Skill

As highlighted in Daniel Bove’s book “Take-Off” section, movements can be broken down into different phases. Some sports may favor or fully omit certain phases.

Examples

Football linemen start each play in a squat position, rapidly exploding into the other teams line. This movement relies on the propulsion phase without the need for unweighting or braking.

Basketball players will use a variety of strategies depending on their position. Jump balls and rebounding may require propulsive only or even a multi-rebound (quick repeat jumps) strategy whereas a jump shot will follow the traditional countermovement jump strategy.

You may choose to program exercises that develop all phases or just one specific phase of a movement under various conditions

Light & fast (Band Accelerated Jumps, Jump Rope

Heavy & slow (Hang Clean, TB Jumps)

Partial or full range of motion (Half Squats, Overcoming ISO’s)

Unweighting

The first thing you’ll want to do here is make sure the athlete is able to comfortably get in and out of the desired position. Often it’s a Assessing the athletes movement This includes;

Flexibility : Do the structures have the ability to lengthen to full range of motion under passive loading. If not, some positional stretches and isometrics should do the trick.

Motor Control : If an athlete can get into a position passively, next you’ll want to see if they can perform the movement under variable conditions; slow/fast, light/heavy. You will have a better idea of their muscles ability to contract and relax at the appropriate time and sequence joint movements.

Some exercises that I like to use to teach and train the unweighting phase

Goblet Squat

Seated Breathing

Braking

A few sources I’ve come across dislike the term “absorbing” force or “eccentric loading” because although they simplify the concept and paint a picture, it’s another example of everyday language not aligning with the mechanical or kinesthetic terminology. To keep it simple, this phase requires rapidly producing force to slow a movement down to either a complete stop or initiate the stretch shortening cycle (SSC). This occurs in a variety of different ways :

Change-of-Direction (cutting, decelerating and landing)

Initiating and Receiving Contact (hockey, lacrosse, & football)

Stretch Shortening Cycle (jump & sprints)

Here we can use different tempos as well as ‘fast force’ exercises from Hunter Eisenhower’s Force System.

Depth Drops

Hurdle Jumps

Drop Squats

Eccentric Deadlifts & Squats

Propulsion

The most common phase has a lot of great options to choose from. The key here is to strategize how you’re going to periodize loads and joint angles to produce the idea result when it matters most. Remember, you’re trying to manipulate the impulse curve using the three factors at your disposal (peak force, time & RFD). I’ll offer some helpful guidelines to follow if you don’t have force plates.

Peak Force : Moderate loads moved quickly

Time : Heavier loads (VBT), accommodating resistance (chains/bands), larger ranges of motion

Rate of Force Development : Body weight or elastic assisted (overspeed)

I prefer to identify which strategy is needed most for their sport and aim to build up to these qualities as we get closer to the season or competition. For instance, our...

Gymnasts will perform heavy loaded jumps (2-DB Jumps, 2-DB Rebound Jumps & conventional strength) during the summer when they’re furthest from the season and work up to low volume movements that accentuate rate of force development (band assisted jumps, depth drop jumps, plyometric hops) during competition season.

Our football players will do heavy olympic lifts, squats and deadlifts during the winter and spring months and transition to fast lifts, curved sprints and change of direction drills over the summer months before training camp.

[Article] ODS System

[Article] Jump Mat vs. Force Plate

[Article] CMJ-Rebound & Drop Jump

[Video] John Pallor Winter Seminar

[Video] Dan Cleather

[Video] Dr. Jason Lake Webinar

[Podcast] Beginners Guide Assessing Force Plates

[Podcast] John McMahon Future of Force Plates...

[Podcast] Hunter Eisenhower The Force System

![[Article] ODS System](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e3c299b74d1a45a8e81a93d/af48e589-7929-4ba8-99b1-1503fcf49e1d/Screenshot+2025-03-13+at+10.33.20%E2%80%AFPM.png)

![[Article] Jump Mat vs. Force Plate](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e3c299b74d1a45a8e81a93d/0d84de17-38f8-4c3c-afbf-b12789167053/Screenshot+2025-03-06+at+11.49.42%E2%80%AFPM.png)

![[Article] CMJ-Rebound & Drop Jump](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e3c299b74d1a45a8e81a93d/1e0d6f69-fc8e-4d99-970c-c45379521621/Screenshot+2025-03-13+at+10.35.01%E2%80%AFPM.png)

![[Video] John Pallor Winter Seminar](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e3c299b74d1a45a8e81a93d/8775ee24-9ae9-4158-9f89-28136d6bfc72/Screenshot+2025-03-06+at+11.38.31%E2%80%AFPM.png)

![[Video] Dan Cleather](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e3c299b74d1a45a8e81a93d/b09ba291-a08d-4252-90a3-86b437206701/Screenshot+2025-03-06+at+11.37.34%E2%80%AFPM.png)

![[Video] Dr. Jason Lake Webinar](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e3c299b74d1a45a8e81a93d/eb964a32-9d52-47b6-94af-21bf98e4585b/Screenshot+2025-03-06+at+11.45.19%E2%80%AFPM.png)

![[Podcast] Beginners Guide Assessing Force Plates](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e3c299b74d1a45a8e81a93d/f321cf8d-aaba-4245-9ef0-f997d3de5cab/Screenshot+2025-03-06+at+11.40.39%E2%80%AFPM.png)

![[Podcast] John McMahon Future of Force Plates...](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e3c299b74d1a45a8e81a93d/dd4f3f4a-1e0d-422e-9e86-47c0baa82cde/Screenshot+2025-03-06+at+11.39.33%E2%80%AFPM.png)

![[Podcast] Hunter Eisenhower The Force System](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e3c299b74d1a45a8e81a93d/38346afa-975f-4898-aff1-1fe3a9acdd61/Screenshot+2025-03-06+at+11.35.07%E2%80%AFPM.png)